Common Worship: Psalm Prayers

My MA dissertation was on the Psalm Prayers (or Psalter Collects) in Common Worship: Daily Prayer. The full title is: Bridging Prayer: A critical evaluation of the psalm prayers in Common Worship: Daily Prayer.

It explores the way these little prayers at the end of each psalm interprets the Psalms themselves.

The dissertation is primarily an attempt to critically analyse what these short prayers have to say. They are offered to us as a source for reflection and, for me, function as “bridging prayers” between ancient Israelite cult, theology and world-view and the Western Christian

interests of today. The intention herein is to ask what kinds of bridges are made (either intentionally or unintentionally). Which themes emerge time and again? What kind of Christology emerges in these Christian readings of the Psalms? Which motifs are repeatedly underplayed or even ignored entirely? How do the prayers link to the liturgical use of the Psalms in different liturgical seasons? The primary intention is to recognise what is there and to consider the picture of the Psalms that emerges when the prayers are considered as their primary interpretative key. Any points of criticism or observation of their shortcomings that emerge from this study are intended to contribute to a richer praying of the Psalms, that is,

prayer that represents a fuller range of meaning which may have been restricted by the prayers as they are.

If you're interested in reading it you'll find it here: Psalm_prayers.pdf (594 downloads)

Christianity, Method and Doctrine

For Christmas I was given Brian McLaren's new book The Great Spiritual Migration: How the World's Largest Religion is Seeking a Better Way to Be Christian. I'm only 1/3 of the way through it but I'm enjoying the opportunity to read the efforts of a prominent "progressive Christian" (not a great term, I know) to articulate a "progressive" vision for Christianity in positive terms rather than simply defining themselves against conservative evangelicalism.

Method: Scientific and Christian

This may be old hat for many, but McLaren makes an instructive parallel between Christian "method" and the scientific method. I'd like to summarise something of what McLaren says about this parallel, and then draw out some of the implications of what he says.

McLaren's general theme is that Christianity needs to make a shift. Christians need to move from defining their faith in terms of assent to a set of particular beliefs (which no-one can quite agree on) to defining themselves in terms of practising the way of love demonstrated by the life, death and resurrection of Jesus. This is where the instructive parallel emerges. McLaren notes that scientists are deeply interested in facts and understanding those facts. They make use of observations about the world to develop theories and they test those theories in order to validate them. Similarly, Christians are interested in beliefs. They use sources of information (Scripture, reason, experience and tradition) to develop beliefs (or doctrines) that help them understand the world. There is a fair similarity between the function of scientific theory within science and the function of doctrine in Christian faith (more on this later). So far, so parallel.

Where the parallel breaks down is the primary commitment of both groups. Scientists are deeply committed to facts. Their observations about the world are the lifeblood of their work. However, their ultimate commitment is not to a particular set of facts, or to particular scientific theories, but to the scientific method. A basic premise of the method is that no theory is final and conclusive. If the evidence is there, then established ways of thinking are discarded in favour of theories that better fit the facts. I recall a story related by Richard Dawkins of an eminent and elderly scientist attending a conference at which a younger colleague delivered a paper. This paper presented new evidence, and a new interpretation of established evidence, that thoroughly undermined the life's work of the older, senior scholar. As the applause died down all eyes were upon the old man. Slowly, he stood up and wiped a tear from his eye. He approached the young scientist with a steely look in his eye. As the old man reached the younger woman he held out his hand to her and shook her hand warmly as he said: "For all these years I have been wrong and you have put me right. Thank you." The standing ovation lasted for several minutes.

The point here is that the prior commitment is to the method over the results. Results are important, but no result is beyond the probing of the method.

By contrast, says McLaren, Christians tend to cling to cherished beliefs. The beliefs are the essence of the faith. Evidence to the contrary tends to be explained away or avoided (indeed, it is often regarded as a badge of honour to keep faith in spite of evidence to the contrary). His argument is that Christians need to prioritise the Christian method over any particular set of beliefs. By "method" I think he means the conscious wrestling with God and his purposes through the lenses of Scripture, reason, tradition and experience, all in the name of seeking to walk in the way of Jesus. Christianity is not a series of beliefs, but a way of life, a method for living fully in the light of God in Christ.

Of course, a cursory skim through Christian history demonstrates that the Christian "method" has always been in operation. Teaching has developed and changed in the light of new experience or new understanding of Scripture. Christians have (largely) changed teaching about women, about slavery or about the nature of Jesus (certainly in the early church). However, McLaren's concern is that the method is not consciously applied in Christianity. While the scientific method is actively employed to grow and develop, the Christian "method" often seeks to deliberately hold back change. Perhaps we ought to be more conscious of being methodical Christians rather than doctrinal Christians.

Some implications and comments...

McLaren doesn't expand his analogy between scientific method and Christian "method" in any great detail but I'm going to try to fill in some gaps.

Firstly, in case it needed saying, it's only an analogy and all analogies are flawed. Scientific and Christian "data" are very different beasts. It's important to go with the spirit of what McLaren is saying rather than the letter.

St Nick punches Arius

Secondly, I don't think McLaren would therefore conclude that doctrines and beliefs are unimportant. Far from it. McLaren and other progressives would affirm the divinity of Christ and the centrality of his atoning sacrifice. Just as in science, the beliefs (or theories) we currently hold are crucial to how we interpret future data. Our doctrine shapes our worldview and we cannot and should not discard it lightly. Many doctrines are ones we can hold with confidence and it is good for us to do. Such doctrines are hard-won and argued-for. If you think current debates about sexuality are bitter then go back and look at Christological debates in the early church. Saint Nicholas is even depicted as punching Arius in the face. (This event almost certainly never actually happened, but it gives a flavour of how hard-fought these controversies were). The point is that doctrine should never reach the status of untouchability.

Finally, it is perhaps worth noting that scientists often go out of their way to seek out new data. Actively thinking about what might disprove a theory is encouraged. Do Christians follow suit? Do we make an effort to hear uncomfortable voices? I know I don't. If we're committed to wrestling with God then perhaps we should be committed to hearing voices from the margin; to hearing voices from the secular world. Some may consider this to be an accommodation to worldliness. I see it as dealing with the world as it actually is, not as our doctrine would like it to be. This doesn't just refer to "experience" of the world. We should also be committed to seeking out more data on how best to interpret scripture.

I wonder what Christianity would look like if we were committed to its core method above its doctrinal formulations?

Morning has broken?

As I write, Britain has voted to leave the EU. The pound has been tumbling against the dollar all night, down to 1985 levels. No-one knows what will happen when the FTSE opens at 8am; anything from 5-10% wiped off the value. The Japanese are panicked because the Yen has suddenly surged.

I genuinely worry for our nation this morning. The simmering resentment that has been coming for a long time (if it's a wake-up call to anyone then you've been asleep for too long) has finally erupted. We'll need amazingly wise and compassionate leadership to hold us together. I fear for the poorest and most vulnerable in our society if we are beginning a bumpy 5-10 year journey to a new relationship with the EU (and the rest of the world).

And yet in Morning Prayer today we pray:

Blessed are you, Sovereign God of all,

to you be praise and glory for ever.

In your tender compassion

the dawn from on high is breaking upon us

to dispel the lingering shadows of night.

As we look for your coming among us this day,

open our eyes to behold your presence

and strengthen our hands to do your will,

that the world may rejoice and give you praise.

Blessed be God, Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

Blessed be God for ever.

It doesn't feel like the "dawn from on high is breaking upon us". It feels more like a creeping gloom. And yet, God's name is to be praised.

Today we remember the birth of John the Baptist. A voice calling in the wilderness. I'm sure lots of people feel like they've been calling in a wilderness this morning. And yet, and yet...

Morning Prayer was hard today. I didn't feel the words I was saying for much of it. But that only makes it more important. I hope we can all pray the Collect for John the Baptist today though:

Almighty God,

by whose providence your servant John the Baptist

was wonderfully born,

and sent to prepare the way of your Son our Saviour

by the preaching of repentance:

lead us to repent according to his preaching

and, after his example,

constantly to speak the truth, boldly to rebuke vice,

and patiently to suffer for the truth's sake;

through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord,

who is alive and reigns with you,

in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

one God, now and for ever.

Amen

5 things I’ve learned about healthcare chaplaincy

I was very fortunate to have spent a week with the chaplaincy team at Hinchingbrooke Hospital over the summer. I got to spend some time with Scott, the lead chaplain (and cracking good bloke), visiting patients and exploring the nature of chaplaincy in a healthcare setting. Here are some of the things I've learned. They don't all necessarily link into each other and they certainly don't form a coherent theology of healthcare chaplaincy but they are there as food for thought!

(Any names used are made up, but the stories are all real.)

1. Wholeness in healthcare

It's easy to treat illness as a purely physical phenomenon. Disease can be caused by bacteria, or we might break a bone, or have a chemical imbalance somewhere. We can therefore assume that these should all be treated in physical terms and nothing more. Of course the physical aspects of illness must be treated in appropriate medical ways but it is a mistake to suppose that medical treatment is (or should be) the only aspect of treatment. Human beings are complex psycho-physical beings and we inhabit influential social contexts, it is therefore important to consider psychological and social (and yes, perhaps even spiritual) aspects of life when looking for healing in the fullest sense.

Yes, we need our bodies patched up, but it helps when our minds and spirits are patched up too. Chaplaincy has much to offer here as a means of healing the person as a whole.

2. A ministry of presence

Glenda was an elderly lady. She'd been in hospital for some weeks. When I first went to see her she told me not to waste my time on her. Why are the hospital expending so much time, energy and money on looking after her when there were many more worthy patients. She'd had her time - what a waste to treat her at her age! Frankly, she felt like a bed-blocking waste of space. After chatting to her for several minutes it became clear that she was far from being a waste of space; she had a loving family, was good-humoured, had an interesting story to tell and had plenty of life in her yet. It was really difficult for the hard-pressed nurses to give her the time and reassurance that she needed but I, from the chaplaincy context, wasn't there to take her pulse or give her medication. Chaplains are there because they are there, simply to be a presence with people and to hear their voice.

Maud was also elderly and a little confused. When I saw her she was fed up and absolutely determined that she was going home. She was worried about her dogs back at home and swore blind that if her husband and son weren't looking after them then she was going give them an earful. I didn't doubt her for a second! It didn't take long to work out that her family didn't visit her as often as they might and this was clearly a source of great pain for her. A chaplain can be there as a simple presence. I couldn't be her husband but she was heard and valued (and wasn't quite so keen to go home).

3. Back to the roots of religion (aka. healing is more than physical)

I'll never forget the moment of revelation that came when the wonderful Mary Earl told me the etymology of the word "religion": re-ligio. The "re" bit means "again" and "ligio" is the same root as "ligament" (that which holds things together). Thus the word "religion" means something like "that which binds together again". At the heart of Christianity is the recognition that we are all broken and fragmented and we all need to be patched up and bound together again. In a hospital there is often a very obvious physical component to being bound back together and most Christians (rightly) leave this to medical professionals. However, it is often the case that our minds, souls, relationships and attitudes need to be bound back together just as much as our physical selves. Times of physical suffering can, perhaps, be triggers to reconsidering other aspects of our lives and chaplaincy work can be central on looking at this. However, there are also times when the physical is simply beyond binding. Some illnesses cannot be healed. Some wounds cannot be mended. For the bereaved death cannot be undone. At these times (more than ever) re-ligion offers a very different kind of healing and chaplaincy should be there to help that process along. (Michael Arditti's novel Jubilate explores this theme better than I could).

4. Our language can betray us

We (or I do, anyway) often use language carelessly, without really thinking through the implications. The example Scott gave was the use of the term "miscarriage". It's a word in common usage and it's fairly clear to all what it means - what's wrong with it? In most contexts, there's nothing wrong with it at all. However, when used with a woman who has recently lost her child it has the potential to have all sorts of connotations of failure or culpability. In that situation, pastoral sensitivity demands that we are aware of the possible implications of the words we use. It doesn't follow that the term "miscarriage" should be removed from regular usage (can anyone think of a better term?); however, a good pastor needs to be aware that such a word has the potential to bring to the surface those thoughts and feelings that may be underneath.

There are further implications here. I am persuaded that the way in which we use language is shaped by our context and serves to shape our future context. Consider the use of language in ethics: take euthanasia as a starting point. The term "euthanasia" itself means "good death" and the immediate implication is that the alternative is something less than a "good death". We could call it "mercy killing", the implication being that to oppose it would be merciless. We could call it "assisted suicide"; of course the term "suicide" has its own unhelpful baggage. None of these phrases are perfect, and that is precisely the point. Language is rarely value-neutral, particularly when related to sensitive subjects. This is not an excuse for ridiculous political correctness in which "failure" becomes "deferred success", but it is a call to awareness and sensitivity to the implications of the language we choose to use.

5. Being real

One final thing I picked up is the importance of acknowledging reality in the chaplain's role. There are times when it is both important and appropriate to offer hope of physical healing; there are also times when perhaps the chaplain needs to encourage the patient to accept that they are not going to get better. The healing of acceptance can be vital (in every sense), but it cannot necessarily happen unless someone is willing to call out the reality of the situation.

In a similar way, when someone has died there are times at which what has happened needs to be named as death. It's easy to use euphemisms to avoid the reality of death; sometimes these are appropriate and helpful, but at other times a chaplain may need to use the D-word in order to help friends and relatives move forward. There is a finely balanced pastoral challenge here: it is easy to talk of resurrection, but without dwelling in Good Friday for a little while the reality of Easter Sunday is just a white-wash. We can't jump the gun and trivialise death by skipping straight to talk of heaven - a good pastor knows how to be with someone in the darkness of Good Friday, naming it as such and supporting them through it.

To conclude...

One particular privilege of my time at Hinchingbrooke was to join Scott in distributing bedside communion. The gentleman in question was in critical care and he had made the decision to discharge himself so that he could return home to die with his loved ones around him. Before he was discharged he requested bedside communion and it was clear to everyone present that the short service (just 10 minutes) was likely to be the final time this man received communion. Scott didn't explicitly say so, but in his manner and inflection of some of the liturgy made the significance and poignancy of the occasion quite clear. At the end the man's wife was in tears and the man was at peace.

This encapsulated the privilege and importance of hospital chaplaincy for me. There was genuine wholeness and healing in the encounter, even though this wasn't externally visible. The man was bound back together as best as he could be this side of death's curtain; the language used was sensitive but profoundly real; at its root it was a simple act of being present and honest about what was going on. Not as easy as it sounds, and incredibly important.

Diary of a Friday in Cambourne

I spent today at Cambourne Church. What follows is a short commentary on some of the things I have seen and noticed...

When I arrived shortly after 9am there are a good number of mums who've just dropped kids off at school. They have come to 19, the church-run coffee house. They take the opportunity to have a little chat and enjoy a cup of coffee (a bargain £1.20 for an Americano). How fantastic that there's a place for people just to pop in and enjoy each other's company in an open and airy space. I'd guess that there are people here who would, in general, never darken the doors of a church and yet here they are. There's nothing massively "churchy" here but people know where they are; isn't it good that this place can offer the simple ministry of being a space where people can gather?

By 9:30 the final few people are sneaking through the door to get into the first meeting of a new Slimming World group. All of us with bacon rolls (£1.40) feel a little guilty. The group is incredibly well-attended which is great, as the organiser looked a little worried that no-one would turn up. They are using the main church hall - a flexible space - and lots of the members had dropped by earlier to have a cup of (black decaf) coffee beforehand. This is a church which is genuinely seeking to serve its community and this is great to watch.

People come and go in small groups throughout the morning. One lady is a bit upset but can use this space to talk with some friends. An elderly gentleman pops in from over the road for a bite to eat and a drink. He chats to the people behind the counter and I have a little chat too (he's a Yorkshireman, friendly chitchat to all is an obligation).

Two businessmen in shirts and ties come in for a coffee and meeting. They are deep in conversation while some kids scream and play up and down the aisle as their mums sit down and chat for a few minutes.

By 11am the last few Slimmers have left the hall. I spot one or two ordering a bacon roll (brown bread) and they clearly take great pleasure in a well-deserved treat. A solitary lady enjoys a tea cake and a book as the light continues to flood in.

The staff here seem to know everybody who comes in and they take the chance to have a little chat with every one. Some of them have more involved conversations and get some support and advice. One volunteer has brought her toddler along while she helps. Her toddler has a fantastic time with some of the other kids.

Shortly after the coffee shop closes the space is filled with mums and toddlers (and a few dads). Everyone eats together, the kids play, parents swap stories and advice. There are some tears and some tantrums (mostly from the kids). Some music and some craft. It's a very congenial atmosphere.

Next is the youth group. Shortly after 4:30pm there are 20-30 teenagers filling the building. Some get a toasty or a milkshake, others play football, some play on the Xbox 360, one even takes me on at chess (and loses). A few of the kids are regulars at church but a lot of them would never darken the doors. Interestingly, there are a fair few who get themselves into a bit of trouble, but here they are involved and enjoying themselves. It's good to watch. There's lots of good banter.

Nothing groundbreaking or new happened today (although the use of Google Forms and an iPad to self-register the kids at the youth club was neat). Lots of things that happened here will have happened all over the place today. None of the things that I've mentioned involved the vicar (although one highlight of the day was to see him running down the high street this morning - a shame he wasn't wearing his dog collar). The day involved normal people doing normal things, and yet there was a real sense that God was at work in these very simple ministries. It felt like the exactly the kind of thing that a local church should be doing and encouraged me greatly.

“Thus says the LORD!” : Prophecy, discernment and Micaiah ben Imlah

In order to complete my mini-series in homage to RWL Moberly I'm going to summarise some of his thoughts about a crucial contemporary issue. When lots of people claim to speak for God (prophecy) how can we go about separating the genuine from the false (discernment). A really helpful case study is that of the interaction between King Ahab and Micaiah ben Imlah in 1 Kings 22. What follows is an exegesis of the passage, which is the climax of the rule of King Ahab in Israel, paraphrasing Moberly's chapter on the topic in his excellent Prophecy and Discernment.

For three years there was no war between Aram and Israel. 2 But in the third year Jehoshaphat king of Judah went down to see the king of Israel. 3 The king of Israel had said to his officials, ‘Don’t you know that Ramoth Gilead belongs to us and yet we are doing nothing to retake it from the king of Aram?’

4 So he asked Jehoshaphat, ‘Will you go with me to fight against Ramoth Gilead?’

Jehoshaphat replied to the king of Israel, ‘I am as you are, my people as your people, my horses as your horses.’

The starting point of the story is the narrator's observation that Israel is in a time of peace with its Aramaean neighbours. This is, implicitly, a good thing, but we learn straight away that Ahab has other things on his mind. His leading question to his fellow king suggests that Ahab has designs on the disputed territory of Ramoth Gilead. There's no particular indication of his motives but the implication is that the power and prestige of Israel (and its king) are more significant factors for Ahab than maintaining peace. Jehoshaphat seems to be aware that Ahab has, in effect, already made up his mind and so gives a diplomatic response.

5 But Jehoshaphat also said to the king of Israel, ‘First seek the counsel of the Lord.’

6 So the king of Israel brought together the prophets – about four hundred men – and asked them, ‘Shall I go to war against Ramoth Gilead, or shall I refrain?’

‘Go,’ they answered, ‘for the Lord will give it into the king’s hand.’

Whether to satisfy his own sense of unease or to ensure that appropriate process is followed Jehoshaphat does ask that Ahab consults his prophets to ensure that YHWH approves of the scheme. Ahab duly takes the advice (he could hardly refuse) and gathers 400 of his prophets in order to obtain the counsel of the LORD. It is obvious now that the king has made his intentions perfectly clear; the prophets know which way the wind is blowing and so tell the king what he wants to hear.

7 But Jehoshaphat asked, ‘Is there no longer a prophet of the Lord here whom we can enquire of?’

8 The king of Israel answered Jehoshaphat, ‘There is still one prophet through whom we can enquire of the Lord, but I hate him because he never prophesies anything good about me, but always bad. He is Micaiah son of Imlah.’

‘The king should not say such a thing,’ Jehoshaphat replied.

That King Ahab's prophets are nothing more than craven toadies looking to further themselves by currying favour with the king is now obvious. Jehoshaphat smells a Jehosha-Rat! This brings the problems of prophecy and discernment out into the open because we have people (a large group, in fact) claiming to speak on behalf of God and yet there is good reason to doubt their authenticity.

Thus, Micaiah ben Imlah comes into the scenario. There is one more prophet through whom we can enquire but the king dislikes him because he "never prophesies anything good about me, but always bad" (read: he never tells me what I want to hear). And so, King Jehoshaphat gently rebukes Ahab and reminds him that Micaiah may still have something worthwhile to say.

9 So the king of Israel called one of his officials and said, ‘Bring Micaiah son of Imlah at once.’

10 Dressed in their royal robes, the king of Israel and Jehoshaphat king of Judah were sitting on their thrones at the threshing-floor by the entrance of the gate of Samaria, with all the prophets prophesying before them. 11 Now Zedekiah son of Kenaanah had made iron horns and he declared, ‘This is what the Lord says: “With these you will gore the Arameans until they are destroyed.”’

12 All the other prophets were prophesying the same thing. ‘Attack Ramoth Gilead and be victorious,’ they said, ‘for the Lord will give it into the king’s hand.’

The narrator now paints a picture for us. The kings in all their splendour at the formal place of justice, with hundreds of prophets of one voice in support of King Ahab, is to be the setting for Micaiah's audience. This is no private audience which might make it easy for him to give his frank and honest view; on the contrary, there is enormous pressure on him to conform. This image will come back in Micaiah's words later on.

13 The messenger who had gone to summon Micaiah said to him, ‘Look, the other prophets without exception are predicting success for the king. Let your word agree with theirs, and speak favourably.’

14 But Micaiah said, ‘As surely as the Lord lives, I can tell him only what the Lord tells me.’

To put the icing on the cake, even the messenger says to Micaiah: "Look, mate, just fall into line and everyone's happy. No need to make a fuss!" He knows exactly what is going on (as does everyone else in the royal court) and wants the easy outcome. However, Micaiah's only concern here is for the truth.

15 When he arrived, the king asked him, ‘Micaiah, shall we go to war against Ramoth Gilead, or not?’

‘Attack and be victorious,’ he answered, ‘for the Lord will give it into the king’s hand.’

16 The king said to him, ‘How many times must I make you swear to tell me nothing but the truth in the name of the Lord?’

We are now left in no doubt about the king's self-serving self-deception. Unexpectedly, Micaiah parrots exactly what the king wants to hear! This demonstrates Micaiah as a masterful communicator, for by saying what is expected he provokes from the king a reaction that reveals that he is aware that perhaps his advisors are simple "yes men". The challenge for Micaiah is to enable the king to admit that what has gone before has been a sham. How hard it is for us to admit when we have allowed ourselves to buy into that which we know, deep down, to be false. How easy to pile deceit upon half-truth upon deception in order to save face! Part of prophecy is to communicate God in a manner than enables us to lay down our ego and acknowledge our failings. Can Micaiah achieve this?

17 Then Micaiah answered, ‘I saw all Israel scattered on the hills like sheep without a shepherd, and the Lord said, “These people have no master. Let each one go home in peace.”’

18 The king of Israel said to Jehoshaphat, ‘Didn’t I tell you that he never prophesies anything good about me, but only bad?’

Micaiah's oracle takes the form of a vision. The king makes two mistakes in understanding it. Firstly, Ahab fails to recognise that the vision is not about him but is about the people of Israel. YHWH's primary concern is for the people who will be left leaderless and the challenge here is to remember his responsibilities before it is too late. Secondly, Ahab fails to respond appropriately. The basic dynamic of Hebrew prophecy is that of response-seeking rather than presenting a fait-accompli; the warning of disaster is intended to provoke a response of repentance (that is, turning from a wrong path) in order that disaster might be averted (see Jonah for a classic example).

19 Micaiah continued, ‘Therefore hear the word of the Lord: I saw the Lord sitting on his throne with all the multitudes of heaven standing round him on his right and on his left. 20 And the Lord said, “Who will entice Ahab into attacking Ramoth Gilead and going to his death there?”

‘One suggested this, and another that. 21 Finally, a spirit came forward, stood before the Lord and said, “I will entice him.”

22 ‘“By what means?” the Lord asked.

‘“I will go out and be a deceiving spirit in the mouths of all his prophets,” he said.

‘“You will succeed in enticing him,” said the Lord. “Go and do it.”

23 ‘So now the Lord has put a deceiving spirit in the mouths of all these prophets of yours. The Lord has decreed disaster for you.’

Again, Micaiah cannot get through to a deluded king by baldly stating that his prophets are only telling him what he wants to hear. The purpose here, again, is to provoke the king's repentant turning from a disastrous trajectory.

It's worth noting the parallel here between the court scene the narrator painted in v. 10. Micaiah is before an earthly court but now describes a heavenly court in which YHWH, not Ahab, is the king. This heavenly court is not intended to be separate, distant and unconnected, but is intended to represent the spiritual reality of what is happening in Ahab's temporal reality. The heavenly court is the spiritual counterpart to the earthly court; it is the other side of the same coin. YHWH's court interprets the true reality of Ahab's court.

Moberly identifies three different levels of interpretation for this vision. Firstly, there's a psychological level. The use of the term "deceive" is Micaiah's attempt to persuade the king that he is being duped by his prophets. By suggesting that God himself is behind the deceptive prophets serves to underline the severity of the deception taking place. Of course, no-one wants to admit to themselves that they are being deceived so by referring to God's involvement there is all the more reason for Ahab not to acquiesce to the duping.

Secondly is the moral level of the vision. Micaiah designates the content of what the 400 prophets say as "sheqer" ('lie', 'falsehood'); the prophetic support of the king's plans is self-serving and lacks integrity. They simply reflect back to Ahab what he wants to hear and in doing so expose his self-interest. There is thus a moral challenge here; not only should Ahab not be duped by the self-serving prophets but he should also recognise his own self-interest and lack of integrity in his ambitions towards Ramoth Gilead.

Finally comes the theological level. By ascribing the proposal to deceive Ahab to God, Micaiah's concern is that Ahab understands that it is not he, Micaiah, who has decreed disaster should this course be followed, but God himself has spoken thus. In continuing along this path Ahab confronts God. Again, the purpose of this "divine decree" is not one of forecasting inevitable disaster but is intended to avert such a disaster. The direct challenge to Ahab's self-will should provoke repentance in order that the divine compassion can be exercised.

24 Then Zedekiah son of Kenaanah went up and slapped Micaiah in the face. ‘Which way did the spirit from the Lord go when he went from me to speak to you?’ he asked.

25 Micaiah replied, ‘You will find out on the day you go to hide in an inner room.’

It is the moment of truth. Zedekiah has an opportunity now to hear the force of Micaiah's words and own up to his self-interest. However, he has a lot to lose if exposed as a fraud and so asks him a challenging rhetorical question. (Indeed, it is the question at the heart of this entire discussion). He asks, in essence, how do we know that you speak for God and not me?

At this point, Micaiah probably knows that he can never argue the others into agreement. There is too much self-interest, too many reputations to protect, for anyone to admit their deceit. He therefore gives a rather cryptic reply. His words are probably best understood as looking forward to a time at which it all comes crumbling down for Zedekiah. The "inner room" is an obscure cubby hole, the kind of place one escapes to when avoiding others (see 1 Kings 20:30). Why would Zedekiah be hiding there? Micaiah's suggestion is that at some point Zedekiah will be exposed for what he is and there'll be some very angry people looking for him. At this low ebb, says Micaiah, you'll do some soul searching and come to acknowledge what you have really known all along; you'll be able to admit to your own lack of integrity.

26 The king of Israel then ordered, ‘Take Micaiah and send him back to Amon the ruler of the city and to Joash the king’s son and say, “This is what the king says: put this fellow in prison and give him nothing but bread and water until I return safely.”’

28 Micaiah declared, ‘If you ever return safely, the Lord has not spoken through me.’ Then he added, ‘Mark my words, all you people!’

The King is not swayed by Micaiah and so Micaiah, in effect, signs his own life-long prison sentence. He acknowledges that if the king returns then everything that he has said has been empty. If he is correct then he'll remain incarcerated. It is surely this integrity that marks out Micaiah as the true prophet. The words of God come at great personal cost to Micaiah; he could so easily have become the 401st prophet and fallen into line (it wouldn't have made a difference to the outcome anyway). However, his acceptance of the implications of his own words and willingness to accept the appalling consequences for himself demonstrate his authenticity.

29 So the king of Israel and Jehoshaphat king of Judah went up to Ramoth Gilead. 30 The king of Israel said to Jehoshaphat, ‘I will enter the battle in disguise, but you wear your royal robes.’ So the king of Israel disguised himself and went into battle.

31 Now the king of Aram had ordered his thirty-two chariot commanders, ‘Do not fight with anyone, small or great, except the king of Israel.’ 32 When the chariot commanders saw Jehoshaphat, they thought, ‘Surely this is the king of Israel.’ So they turned to attack him, but when Jehoshaphat cried out, 33 the chariot commanders saw that he was not the king of Israel and stopped pursuing him.

34 But someone drew his bow at random and hit the king of Israel between the sections of his armour. The king told his chariot driver, ‘Wheel around and get me out of the fighting. I’ve been wounded.’ 35 All day long the battle raged, and the king was propped up in his chariot facing the Arameans. The blood from his wound ran onto the floor of the chariot, and that evening he died. 36 As the sun was setting, a cry spread through the army: ‘Every man to his town. Every man to his land!’

37 So the king died and was brought to Samaria, and they buried him there. 38 They washed the chariot at a pool in Samaria (where the prostitutes bathed), and the dogs licked up his blood, as the word of the Lord had declared.

And so, the king rides out to battle. It is notable that he does not act as a king confident of victory. He hides himself among the rank and file; a man in fear of his life and aware that he doesn't want to be a target. His end comes quite by accident and his final few hours allow him only time to see his armies defeated. This is surely the equivalent to Zedekiah's "inner room", the time at which the truth of Micaiah's prophecy becomes painfully clear to him in every respect.

Conclusions

So what are we to conclude about prophecy and discernment? It is surely the case that the genuine prophet speaks truth to power at the risk of great cost. The central dynamic of the story is around self-will and integrity. The prophetic call to Ahab is to dig deep and accept that his own intentions don't conform to the moral will of God. This isn't easy for any of us, and no-one likes to be told that they are being self-serving.

Who are you? Are you like Ahab? When you ask a question do you encourage people to tell you what you want to hear? Are you willing to listen when someone exposes your self-interest or do you do all you can to protect that interest? When you listen to the still, small voice inside are you able to change when it goes contrary to your own will?

Are you like Zedekiah? Do you tell people what they want to hear in order to feather your own nest? Do you carefully observe which way the wind is blowing and ensure that you catch that breeze? When someone challenges your ideas do you accept that you might be self-serving or do you seek to discredit dissenting voices in order to protect your own position?

Are you more of a Jehoshaphat? Are you aware that the wrong things are happening for the wrong reasons? Do you ask a few questions but then go along with it when the chips are down?

Or are you a Micaiah, willing to speak uncomfortable truth to power, even at great cost?

I'm pretty sure I'm primarily like Ahab and Zedekiah. It's so easy for me to know deep down that I'm wrong about something and yet prefer to dig my feet in and argue, shame and discredit nay-sayers rather than repenting and admitting my fault. It's always straightforward to tell people what they want to hear and avoid difficult conversations. I do it all the time, expecting someone else to take on the challenge. This is, for me, why church community is so vitally important. We (or I, anyway) need an environment in which people can be given the grace to enable repentance and change. It's vital to have a community of faithful critique in which we can, lovingly, challenge our brothers and sisters. This takes practice but, as Jesus put it: "This is the verdict: light has come into the world, but people loved darkness instead of light because their deeds were evil. Everyone who does evil hates the light, and will not come into the light for fear that their deeds will be exposed. But whoever lives by the truth comes into the light, so that it may be seen plainly that what they have done has been done in the sight of God." (John 3:19-21) Living in light is hard so let us be prophetically bold and humble in discernment.

Eli, Samuel and the nature of priesthood

Continuing my series on repeating the wisdom of Professor RWL Moberly I'd like to share with you some insights on what 1 Samuel 3 might have to tell us about the nature of priesthood. What follows will take the form of a fairly straightforward exegesis of the passage as I remember Professor Moberly presenting it with a few conclusions of my own...

Continuing my series on repeating the wisdom of Professor RWL Moberly I'd like to share with you some insights on what 1 Samuel 3 might have to tell us about the nature of priesthood. What follows will take the form of a fairly straightforward exegesis of the passage as I remember Professor Moberly presenting it with a few conclusions of my own...

The boy Samuel was serving God under Eli’s direction. This was at a time when the revelation of God was rarely heard or seen. One night Eli was sound asleep (his eyesight was very bad—he could hardly see). It was well before dawn; the sanctuary lamp was still burning. Samuel was still in bed in the Temple of God, where the Chest of God rested.

I take it from this that the people of Israel were in a time of relative spiritual darkness. The reference to Eli's bad eyesight is probably an extension of this. Why else would the narrator mention it unless he wants the reader to understand that God's priest is just as spiritually blind as everyone else? However, in spite of all this the narrator notes that "the sanctuary lamp was still burning", perhaps a sign that the light hasn't quite gone out on Israel's awareness of God.

Then God called out, “Samuel, Samuel!”

Samuel answered, “Yes? I’m here.” Then he ran to Eli saying, “I heard you call. Here I am.”

Just like that. Out of the blue. God calls to Samuel! What do we notice about Samuel's response? Firstly, there is no surprise. Samuel doesn't awaken and say to himself, "Whose voice is that? I don't recognise it!" The translation here makes it clear why: the voice he hears isn't strange, it is Eli's.

Secondly, we can then note that when God calls to Samuel he does it in a familiar way. When God is revealed to someone this revelation may well resonate with something familiar. It is extremely rare for God's voice to boom down from heaven and sometimes it is incredibly difficult for us to listen to the still, small voice. It therefore makes sense that God may choose to speak to us through others and that seems to be what's happening here.

Eli said, “I didn’t call you. Go back to bed.” And so he did.

Eli's response further emphasises his own spiritual blindness. Rather than recognising what has happened Eli is rather abrupt. There's probably a challenge here to the priesthood of all believers: How often do we recognise God speaking to someone through us? How often do we say, in essence, "I didn't call you", instead of perceiving that God has called?

God called again, “Samuel, Samuel!”

Samuel got up and went to Eli, “I heard you call. Here I am.”

Again Eli said, “Son, I didn’t call you. Go back to bed.” (This all happened before Samuel knew God for himself. It was before the revelation of God had been given to him personally.)

The same pattern recurs and this time the narrator makes explicit what was merely implied earlier: Samuel doesn't know God for himself. It's no great surprise that Samuel doesn't know what is going on, how could he? We don't often get to know someone new without an introduction!

God called again, “Samuel!”—the third time! Yet again Samuel got up and went to Eli, “Yes? I heard you call me. Here I am.”

That’s when it dawned on Eli that God was calling the boy. So Eli directed Samuel, “Go back and lie down. If the voice calls again, say, ‘Speak, God. I’m your servant, ready to listen.’” Samuel returned to his bed.

Eli's spiritual fog finally begins to lift. He finally realises what is happening! At this point Eli takes on a position of great power and authority and there is, therefore, also a great risk. Power and corruption often go hand-in-hand and this situation is no different. Eli takes on the function of the voice of God for Samuel; when God speaks Samuel hears Eli's voice and it quickly becomes possible now that when Eli speaks Samuel understands it to be God speaking.

I'm sure that lots of us could identify fathers (or mothers) in Christ who have been incredibly influential in our early journey of faith. It seemed at the beginning that everything they said was like something coming from God. When in that position there's always a risk of the abuse of power. I'm afraid that church history has plentiful examples of those in positions of power turning their authority into an opportunity for self-aggrandizement. The person through whom God speaks can often end up mistaking themselves for God.

So how does Eli respond when he recognises his own status in the eyes of Samuel? He does exactly the right thing by pointing beyond himself to the bigger reality that is calling Samuel. He shows Samuel the way forward and invites him to participate in the bigger reality of God.

Then God came and stood before him exactly as before, calling out, “Samuel! Samuel!”

Samuel answered, “Speak. I’m your servant, ready to listen.”

Note that now God's relationship with Samuel is much more direct: "God... stood before him". Even though he's been there all along Samuel is now in a position to see him.

What do we take away from all of this? Firstly, the role of the priest is always to point forward to God. There's always a human temptation to make ourselves important and to lift ourselves up. Eli teaches us that we need to direct people to a bigger reality. Our thoughts, ideas and projects are never ends in themselves (however much we'd like to think they are).

Secondly, we ought to learn to recognise when God is speaking through us (and be careful with it). Sometimes we can inadvertently find ourselves in positions of spiritual authority (this certainly applies to those in church leadership and youth work roles). Even someone we consider to be just a friend can be greatly influenced by the things we say. Therefore, we all need to regularly examine our own hearts. Do the things we do and say point beyond us to the resurrection life and union with Christ? Or do they subtly serve to further our own interests and re-enforce our own authority? Does the way we interact with others build the kingdom of God or our own personal kingdoms? I'll certainly confess to knowing how easy it is to dress up my own self-interest in pious words and the "right" language and how easy it is to be self-deceptive on this front.

Thirdly, we ought to be aware (and appropriately non-idolatrous) of our own "god parents". When we find someone we really "connect" with it's easy to read everything they say as divinely inspired. I'm on a bit of a Richard Rohr binge at the moment. I love him. His daily meditations always seem to hit my nail right on the head. However, I'm aware that I need to check myself regularly. Is my appreciation of Fr. Richard leading me deeper into the likeness and love of Jesus or into the likeness and love of Richard Rohr. If it's not the former then he becomes an idol instead of a priest. I know people with similar warmth towards Rob Bell, Mark Driscoll, Brian McLaren, Scot McKnight, Pope Francis and many others. These are all good in and of themselves but idolatry is dangerous.

The final conclusion, drawn from the previous two, is that we need to hold each other to account. It's dangerously easy to be in a position of authority and not recognise it; there's a fine line between admiration and idolatry. I don't know many people who like challenging others but we need to do it. With love. So the next time you see me, please ask me: "How has Richard Rohr encouraged you further into the likeness of Christ this week?" If I can't answer you then we need to have a conversation. Ask me: "What have you done this week to point Matthew towards Jesus?" If I can't answer you then please have some ideas ready to help me out! (Seriously, what do you do with a six month old?)

Remember: we're all priests. It's not just people in a dog-collar who should be pointing towards Jesus and saying, "See! The Lamb of God!"

On “death” in Genesis 3 (or, did the Serpent get it right?)

What follows is a precis and discussion of the wonderful R W L Moberly's essay entitled "Did the Serpent Get it Right?" (Journal of Theological Studies 39, no. 1 (1988), pp. 1-27). I often find myself coming back to this exposition of Genesis 3 because it is incredibly important for how we understand the human condition and, therefore, the rest of the Bible. A close and careful reading of what happens in the Garden of Eden illuminates much about the "problem" that Christianity is attempting to solve and has significant theological implications.

(Note: My summary is based on memories of a lecture almost 10 years ago, and a subsequent reading of the article about 9 years ago. My apologies go to Professor Moberly for any inaccuracy or lack of nuance.)

Setting the scene

The key scene-setting moment comes in Genesis 2:16-17. God has just created Adam and his first commandment to Adam (in this version of the creation story) is a positive one: "You may freely eat of every tree of the garden!" (NRSV) but there is one minor restriction: "but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat". God doesn't particularly justify this prohibition (creator knows best and we should trust him on this) but offers Adam a warning: "for in the day that you eat of it you shall die". It is the nature of this death that needs some discussion, but we'll come to that later. All that needs to be said for now is that the implication is that there will be some fairly immediate consequence ("in the day").

Enter the serpent...

The beginning of Genesis 3 sees the entrance of the Serpent. Much could be said about the way the serpent twists God's words (the positive commandment with a single prohibition becomes purely prohibitive in the mouth of the serpent: ‘Did God say, “You shall not eat from any tree in the garden”?’) but this would be a diversion from the main purpose of this post.

What is really of interest is Eve's correction of the serpent. She rightly notes that God says they can eat of any tree, except for one (and, for some reason, adds an extra prohibition about touching the tree). Eve clearly knows the rules God has set out. However, at this point, the serpent flatly contradicts God's warning about eating from this tree: But the serpent said to the woman, ‘You will not die; for God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.’ From this point on the tension of the story is established. On one hand, God has declared emphatically that "in the day that you eat of it you shall die" while the serpent contends that "You will not die" and implies that God's prohibition is a form of protectionism (we don't want these human beings to have our knowledge). So who is right? The only way to find out is for someone to eat the fruit... Cue Eve.

Eating the fruit

So, the scene is set. Who was right? God or the serpent? If God was right, then we expect to see the fairly immediate death of those who eat of the forbidden fruit. If the serpent is on the money then we expect to see no death and instead we'll find that eyes are opened. Let's see what happens:

So when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate; and she also gave some to her husband, who was with her, and he ate. Then the eyes of both were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together and made loincloths for themselves. (Genesis 3:6-7)

On face value, it appears that the serpent is the one telling the truth here. Not only do Adam and Eve not die on that day (indeed, Adam lives to the ripe old age of 930! [Gen 5:5]), but also the serpent's prediction about eyes being opened come true! What are we to make of this? Do we have a situation in which the very first things God says to human beings is just self-serving lies and deceit? Is it the case that the shrewd serpent is the voice of truth? Surely a religion based on a deceptive, possibly bullying God deserves little attention. Therefore, if we want to save this story and avoid the Judaeo-Christian tradition falling down before it's begun we need to understand this story a little more carefully.

Did God *really* say...?

Let's reconsider what God says to Adam in Genesis 2:

And the Lord God commanded the man, ‘You may freely eat of every tree of the garden; but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall die.’

There are a number of ways to understand this command other than the wooden version we've already discussed. Some are more satisfactory than others.

1. Adam and Eve were immortal prior to this moment

I've heard it suggested that Adam and Eve were intended to live forever. Therefore, when God says "in that day... you shall die" it is not that they will literally drop dead that day but that the moment they eat of the fruit mortality comes to them. Previously they had been immortal; now the possibility of death is upon them. They don't die that day, they become able to die. I can see the appeal of such an approach but I end up rejecting it for several reasons.

Firstly, there is no suggestion prior to this moment that Adam and Eve were created with the intention that they might live forever. Secondly, at the end of Genesis 3 God is worried that Adam and Eve might "reach out his hand and take also from the tree of life, and eat, and live for ever". This surely implies that Adam and Eve may have had the possibility of living forever but now do not. The possibility of becoming immortal being taken away is rather different to the transition from immortality to inevitable death.

2. We need to reconsider what God means by "death"

In recent years the concept of "quality of life" has been used in an increasing range of contexts. I've heard the idea used to justify abortion (the child will have a poor quality of life and so abortion may be more loving), I've heard it used to justify euthanasia (her quality of life is so limited that she would prefer to die). I've also lost count of the number of times I told my parents to "get a life" when I was growing up. By this of course I didn't mean that they lacked life in a biological sense; my outburst was related to my perception of their quality of life. Christian Aid have a wonderful slogan: "We believe in life before death". All of these examples serve to suggest that in many senses "life" and "death" are not simply binary options (ie. a person is either alive or dead). In a very real sense the concept of "life" is on a spectrum and we can rightly use the term "death" to refer those things that lessen our life in some way. When someone says, "A little piece of me died when..." they do not mean that they suffered necrosis of part of their body, they refer to an event diminishing the fullness of their life.

With that in mind it seems reasonable to ask whether God's proclamation that Adam would "surely die" is a reference not to biological death, but to death in this other sense. Let's consider what happens in the immediate aftermath of the eating...

Firstly, "they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together and made loincloths for themselves". There is an instant sense of a loss of innocence. Whereas they had previously been naked and had been comfortable with their nakedness, they now have a sense of shame. As such, there is an immediate death in Adam and Eve's relationship with their selves; they are not longer unified beings but are in conflict with themselves. Their life is diminished. Death has come upon them.

Secondly, "They heard the sound of the Lord God walking in the garden at the time of the evening breeze, and the man and his wife hid themselves from the presence of the Lord God among the trees of the garden". What had previously been a close and intimate relationship has become fractured. Adam and Eve are now afraid of God, aware of their shame, and the relationship is now an uncomfortable one. Life is diminished. Death has come upon them.

Thirdly, "He [God] said, ‘Who told you that you were naked? Have you eaten from the tree of which I commanded you not to eat?’ The man said, ‘The woman whom you gave to be with me, she gave me fruit from the tree, and I ate.’" What is Adam's response to God's (correct) accusation? He blames the woman. And so begins the process of shifting blame and responsibility away from ourselves and onto others. Adam and Eve were previously united but now use each other as objects of blame. Their relationship begins to break down. Life is diminished. Death has come upon them.

Finally,

Cursed is the ground because of you;

in toil you shall eat of it all the days of your life;

thorns and thistles it shall bring forth for you;

and you shall eat the plants of the field.

By the sweat of your face

you shall eat bread

until you return to the ground.

The last outcome of their disobedience is that Adam and Eve have a broken relationship with the natural world. Whereas once there was a sense of harmony, now there is a sense of discord. Life is diminished. Death has come upto them.

It is worth noting that the first three of these outcomes (and arguably the fourth also) are not "punishments" from God, but natural consequences of their actions. God does not make Adam and Eve at war with themselves, God and each other; this conflict is the natural outcome of what they have done.

So why does this matter?

This story sets the tone for everything that follows. In many ways it outlines the "human condition" and, therefore, the way we interpret it has implications. If we understand the story as being about biological death entering the world through the sin of Adam then we can end up with a Christianity that is overly focused on "pie-in-the-sky-when-you-die". The problem for humans (in this understanding) is that we are all going to die and need to do something about it. However, it seems to me that Jesus is much more concerned with the richness of our lives in the here-and-now. Broken relationships that diminish our lives are in dire need of healing. Our fractured sense of self, in which we find ourselves in conflict with our own desires, needs binding back together. Our distant and fearful relationship with God needs to be made intimate once again. Our troubled relationship with our natural environment needs to be changed.

The insight of Christianity is that we cannot rebuild these relationships purely in our own power. That is why God comes to us in the person of Jesus to enable our attitudes and egotism to change. This is no easy task and Jesus demonstrates just how far God will go in order to bring his children home into a right relationship with him.

"Salvation" means "healing", not simply "going to heaven when you die". I, for one, need salvation for the healing of all of my fractured relationships. "Religion" means "to bind back together" (re-ligio - think "ligament"), not simply a set of rituals or beliefs. I, for one, need to be made whole again. When we make Genesis 3 about a binary choice between "life" and "death" we lose what Jesus says about coming to bring "life in all its fullness". Let's seek Christianity in a way that makes "religion" about wholeness and "salvation" about healing our broken lives, not just a set of doctrines to which we must subscribe in the hope of an eternal reward.

Comments are very welcome. This post is brief and necessarily limited and incomplete to some degree. If there's anything I need to clarify/tighten up I'd appreciate the help!

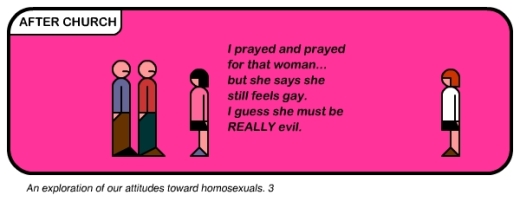

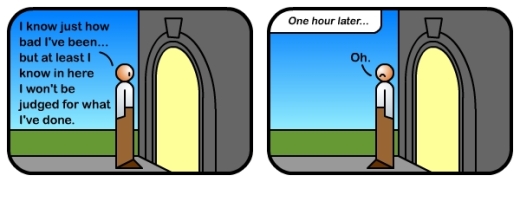

ASBO Jesus

My copy of The Ongoing Adventures of ASBO Jesus has just arrived. It's a series of cartoons, based on the ASBO Jesus blog, that present Jesus as the radical, prophetic Jewish carpenter that many Christians would prefer him not to be.

The first cartoon in the book presents a man praying: "Dear Lord, thank you that I am not a homo, foreigner or mental. Amen." This kind of challenge to religious hypocrisy is the sort of stuff I love.

I also loved this:

I can't find the cartoon but there's a great one in which one guy says to another: "I think God is saying..." and the other guy says, "I hope you don't mind me saying, but God sounds rather like you."

It's mostly challenging and incisive. The blog also has some interesting discussions of the cartoons. Well worth a read!

SlutWalk: a helpful way forward?

I've been mulling over the concept of a SlutWalk for a little while now. The whole idea is rather troubling for me (and perhaps that's a good thing), but I can't help feel that, while the root message is important, the means used are ultimately unhelpful.

Let me state clearly at the outset that I thoroughly agree with the notion that sexual abuse is never acceptable. It is unacceptable to "blame" a girl (or boy, for that matter) for being the victim of sexual assault on the grounds that they were dressed in a certain way. The message needs to be clearly heard that sex is a gift that must not be misused and cannot be taken from an unwilling victim.

It cannot be justified to say that a victim of sexual assault was "at fault" because of the way they were dressed. The causality is nothing like so clear cut and any implication that it is must be rejected. However, at the same time it is simply not the case that the way we dress makes no difference to the way others perceive us. Of course it does, and indeed there is nothing inherently wrong in allowing the way someone presents themselves to inform one's assessment of that person. It is nonsense to suggest that we should be neutral in our dealings with other people. Humans are meaning-making beings and we seek to understand the things that we encounter; it is right and proper that we should make use of all the information available to us in doing so. This includes the content and tone of a person's speech, their manner, their body language and yes, their attire.

Now, it does not follow that a man should observe a girl's clothing and make a judgement that she is "up for it". Such a judgement would be rightly condemned if this man were to forceful sexual advances as a result of it. However, it may be legitimate to ask oneself about the message that someone's attire is intended to convey. It is disingenous to say that our clothing says nothing about us at all. Who would not look at a bishop in full episcopal dress and not formulate certain assumptions (note, not conclusions) about aspects of that person's character and thinking? Who would not see a policewoman walking down the street and infer (rightly or wrongly) that she was a law-abiding citizen? Who would not walk past a gang of hooded teenagers and wonder (probably wrongly, but wonder none-the-less) about whether they were up to no good?

The problem we have is about the extent to which these judgements (often unconscious) are justified. We have to ask ourselves where these ideas come from and whether the stereotypes that lie behind them are legitimate. Often they are not. Unfortunately, the perception that a girl dressed in a certain way is "fair game" is a widespread one. The issue is how we deal with this perception.

My hunch is that we have a problem in society with increasingly making a separation between "sex" and "love" (or, at least, committment). Of course it would be absurd to hark back to an age in which sex was purely the preserve of the marital bed. Promiscuity has always existed, fleeting sexual encounters have always taken place, haystacks have always been the setting for an impromtu romp. However, there has been a change in the public perception of casual, uncommitted sex, and this leads to a problem.

Let's consider a recent Lynx advert. It starts with a couple in bed enjoying the warm glow of morning. Over the next 40 seconds we see these two retrace their steps back to the supermarket where they had met the day before. Before they part we see the fleeting glance of those who never expect to see each other again. At this point the words appear: "Because you never know when" and cuts to a man spraying Lynx deodorant. The message is clear: if you have a chance encounter in a supermarket you want to smell nice because you never know where it might lead. Presumably the logic of the advertsers is that people want to meet strangers and have sex with them at the drop of a hat; the idea of a random sexual dalliance is good and we want to place our product in the creation of it.

I'm exremely uncomfortable with this.

I'm yet to meet anyone who, when the chips are down, has said: "I love meeting someone in a club, going home with them, having sex, and then leaving the next morning". Of course, people brag about such happenings but I've never spoken to someone who has set the machismo aside and still said the same thing. I have, however, met people who have been hurt by such flings and also people who have become trapped in cycles of unhappy promiscuity. This may well be to do with the circles I move in. If anyone would like to argue with me on this point I'd be interested to hear it. My questions are, when did we get to this point? When did we agree that it is a good idea for one of the most intimate things a human being can do to be treated with such a casual attitude? Where does this leave the male perception of women and their value and worth? How might such an attitude encourage a man to even ask himself if the girl he is dancing with is "up for it"?

Oh dear me, I've rambled. Where does this leave the SlutWalk?

If you've followed me this far then perhaps you'll agree that simply asserting the right to wear what one likes doesn't necessarily resolve the problem. While most men probably do need to reflect on their attitude to women and their sexual objectification, it is perhaps unhelpful of women to assert their right to dress in a sexualised way. This does nothing to challenge the perception that casual sex is a good thing. While men do need to hear that "No means no", perhaps women need to acknowledge that the way they dress can potentially propagate the idea that they are objects available for casual sex.

It is not as simple as "It's my hot body, I do what I want" (as one placard read). Just as it's neither kind nor helpful to parade your glass of wine in front of an alcoholic, it's not a helpful step to assert one's sexuality in front of someone who measures their own self-worth in notches on a bedpost. The way we act and present ourselves affects other people and the message that it's "their problem" if they can't handle it only holds a limited amount of weight. We need a solution to the problem of the increasing meaninglessness of sex in society.

I don't think I've expressed myself very well here. If I haven't then I'm sorry. However, I strongly feel that the language of "rights" is often unhelpful when it's divorced from the language of responsibility and I fear that the SlutWalk movement, though laudable in many ways, will not lead to a long-term solution to sexual violence.